roperly managed self-storage occupancy maximizes an operator’s bottom line, but misconceptions persist about the best occupancy strategy. Most industry operators try to keep occupancy between 90 percent and 95 percent. Some try to maintain 100 percent occupancy. Though it might seem counterintuitive, you are losing money if you keep your facility completely full. This leaves you with two options: add new units or raise rental rates.

How to measure occupancy is as important as maintaining the ideal occupancy. The two main ways to measure it are physical and economic. We report data in the Self-Storage Almanac based on physical occupancy. This measures the number of units rented. For example, if you have 100 units and 90 are occupied, then your facility’s physical occupancy is 90 percent.

By contrast, economic occupancy is based on the gross potential income you are collecting. Gross potential income factors in any concessions or discounts you give your customers. For example, if you have a 100-unit facility with 90 units rented and you give customers a one-month-free concession on the remaining 10 units, then your facility’s economic occupancy is 80 percent. This is because you collected no rent for one month on those 10 units, which decreased your income accordingly.

Kenneth Nitzberg, chairman and CEO of Devon Self Storage, based in Emeryville, Calif., says 85 percent occupancy is considered stabilized, and 90 percent is better. But too much above 90 percent is undesirable. “Because what that tells me is that we aren’t raising rents often enough or high enough to force a couple of people to move out or pay the higher rents,” Nitzberg says.

“However, some are optimistic that as new home sales eventually find a bottom and new storage development slows, we will begin seeing improvements in storage occupancy and street rates,” according to the report.

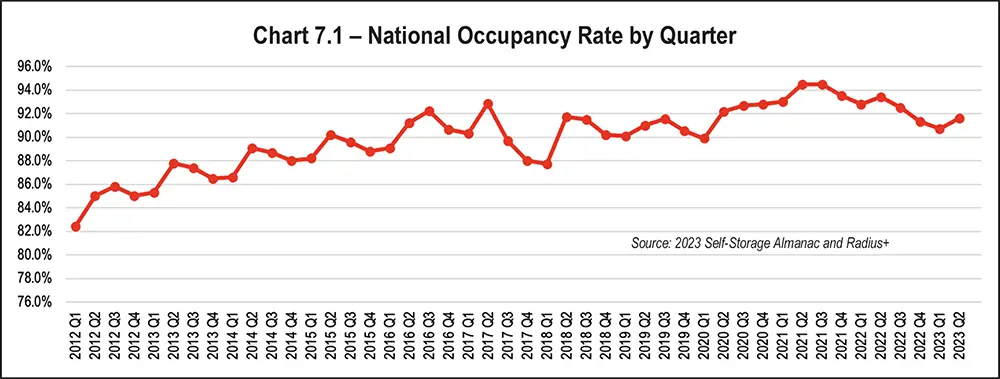

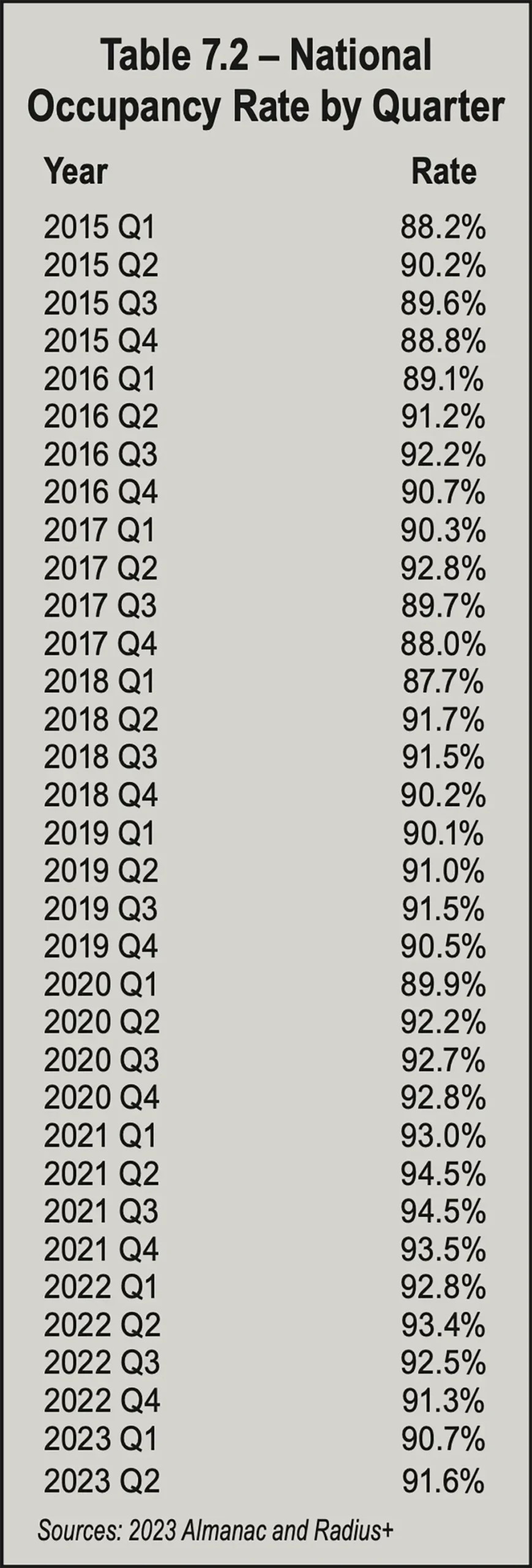

Digging deeper into the quarterly numbers in Table 7.2, which tracks Q1 2015 through Q2 2023, the low mark was 87.7 percent in Q1 2018. The high mark was 94.5 percent, which occurred in both Q2 2021 and Q3 2021. Quarterly rates increased from Q1 to Q2 throughout the period, mostly decreased from Q2 to Q3 and from Q3 to Q4; and showed an even mix of increases and decreases from Q4 to Q1. Overall, occupancy rates stayed mostly in the 80s from Q1 2015 through Q1 2016 and stayed mostly in the 90s from Q2 2016 through Q2 2023 but dipped into the 80s during four quarters of that period.

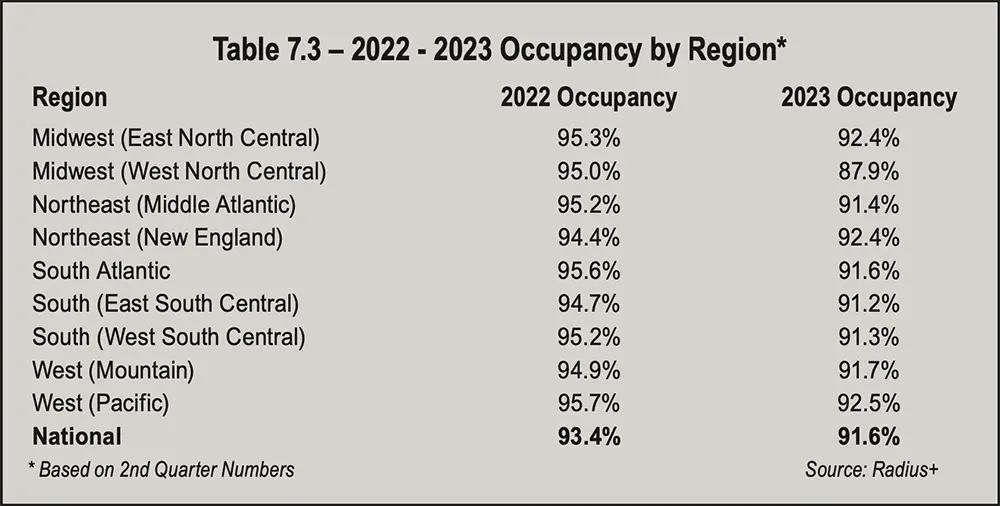

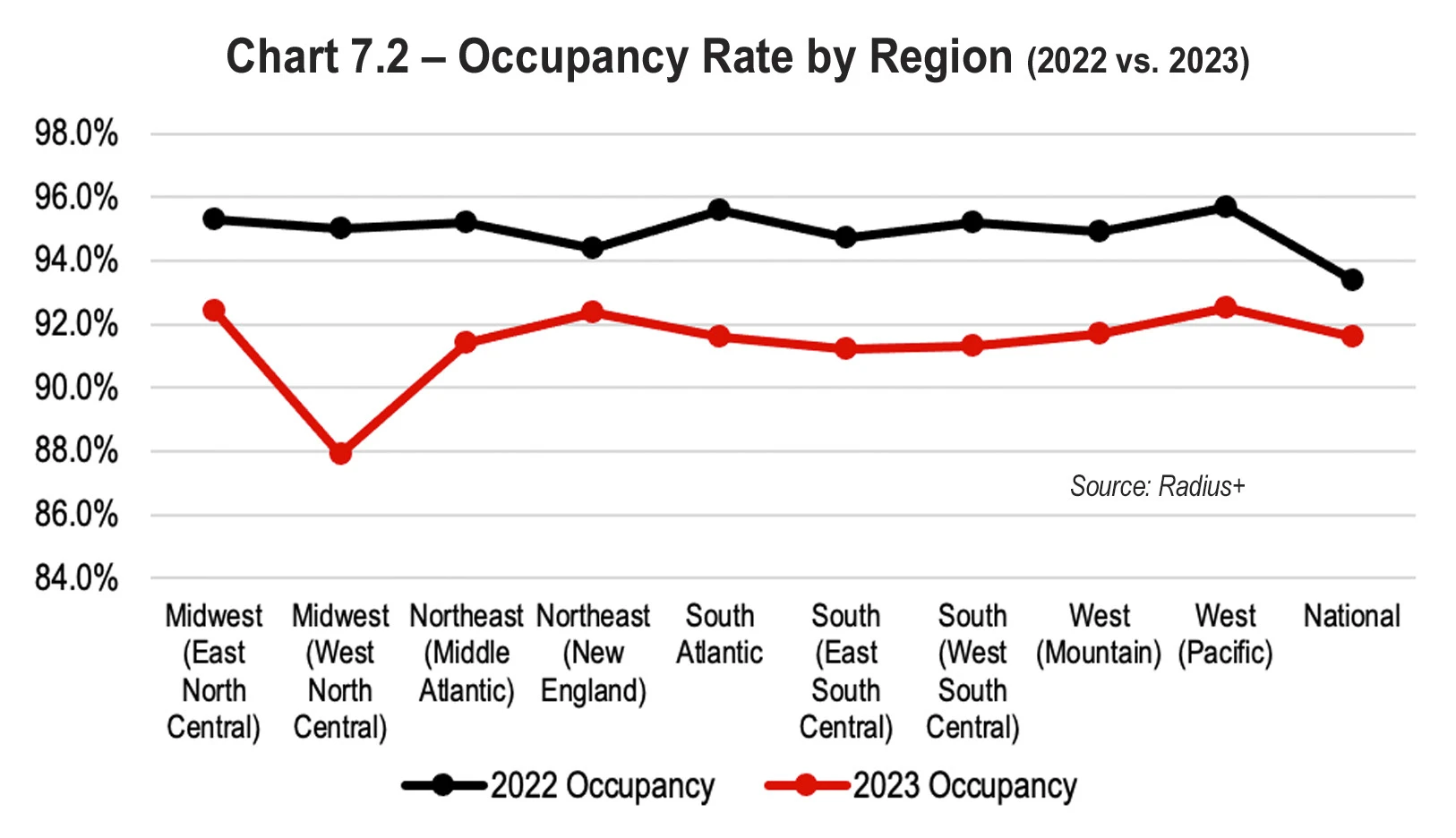

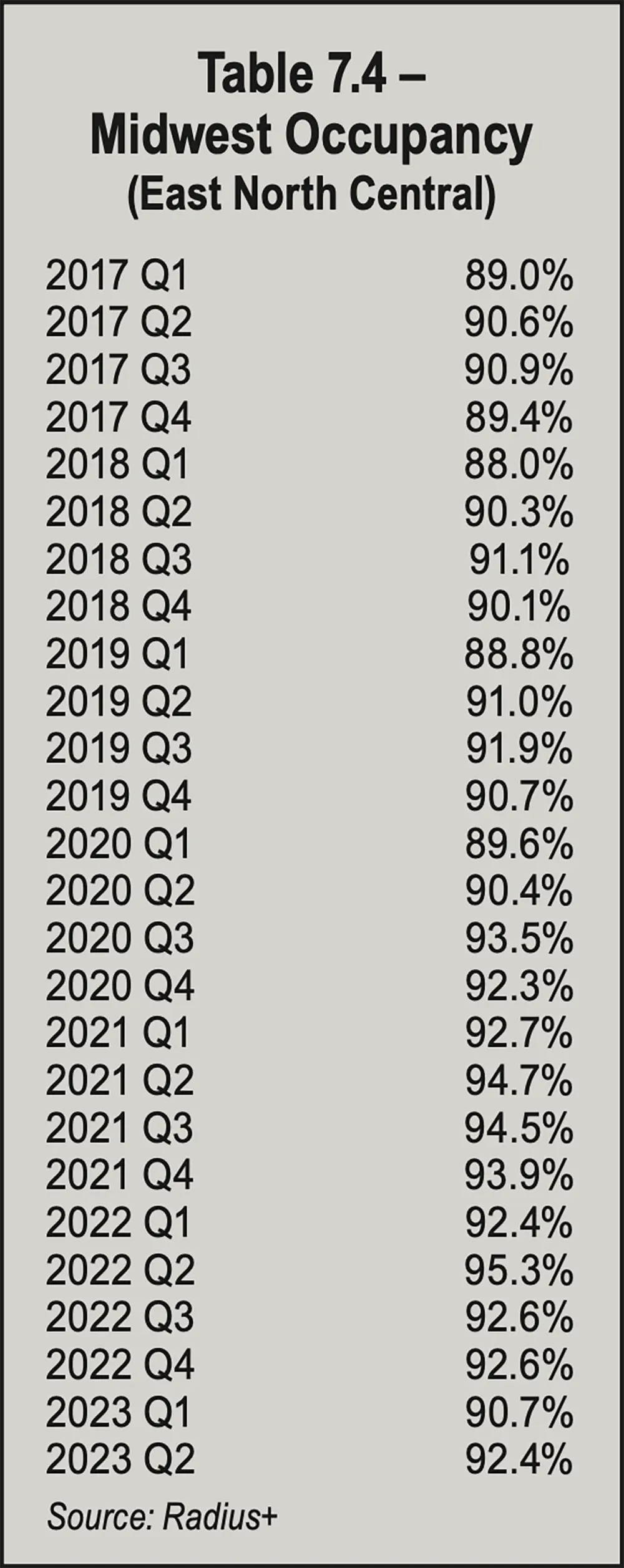

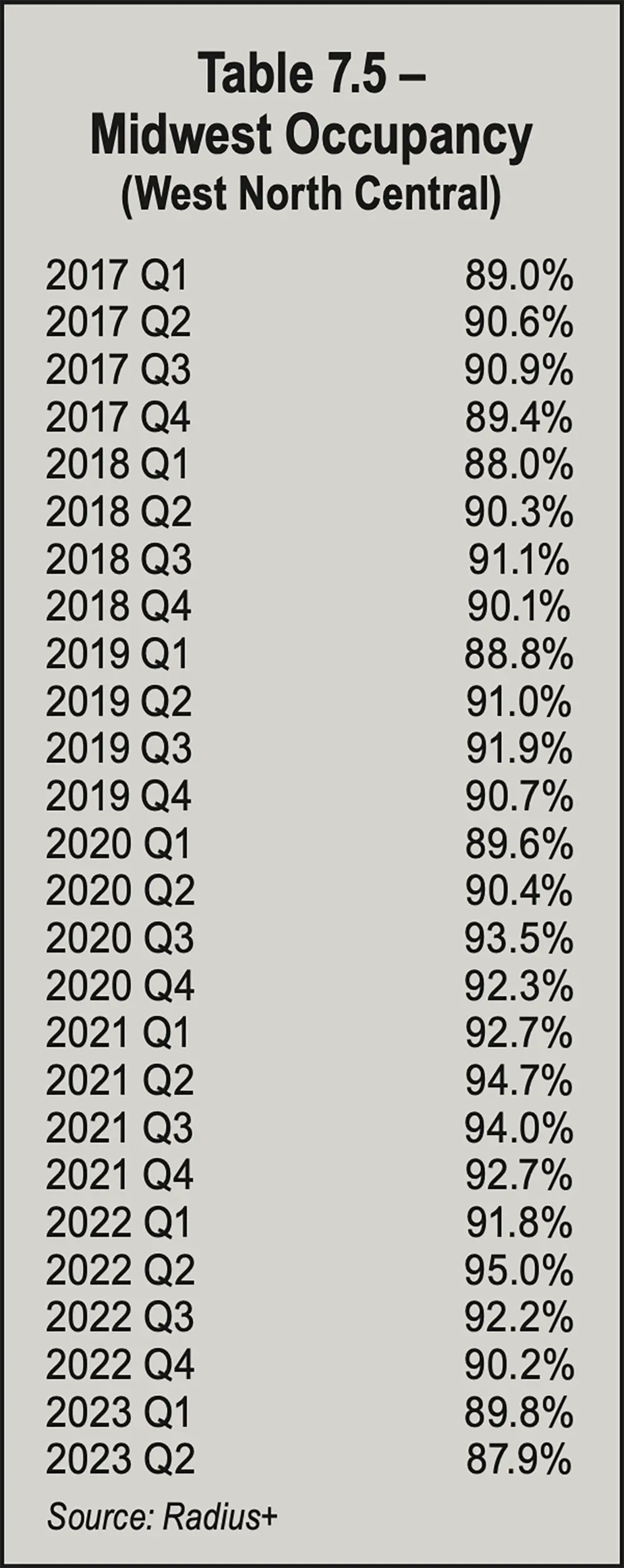

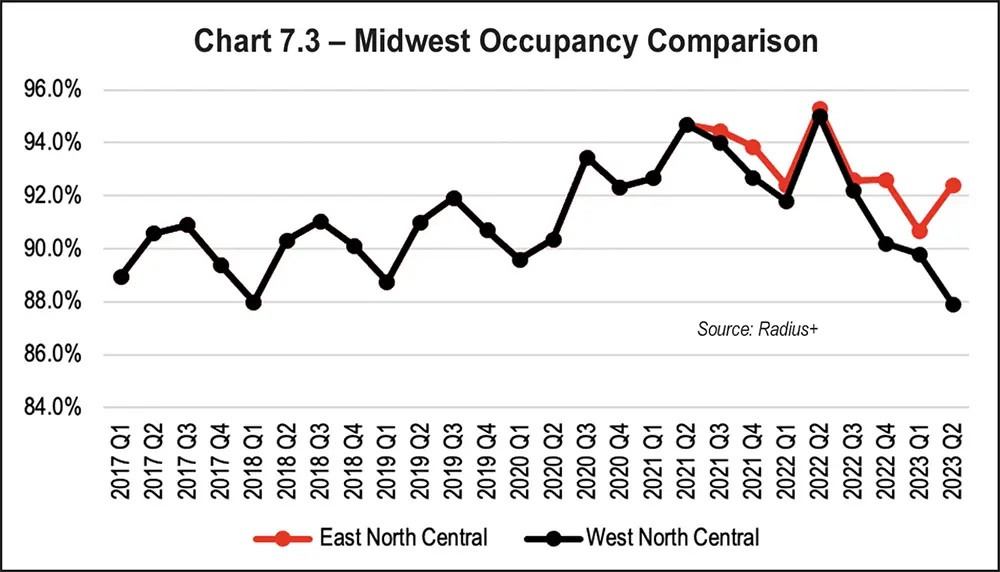

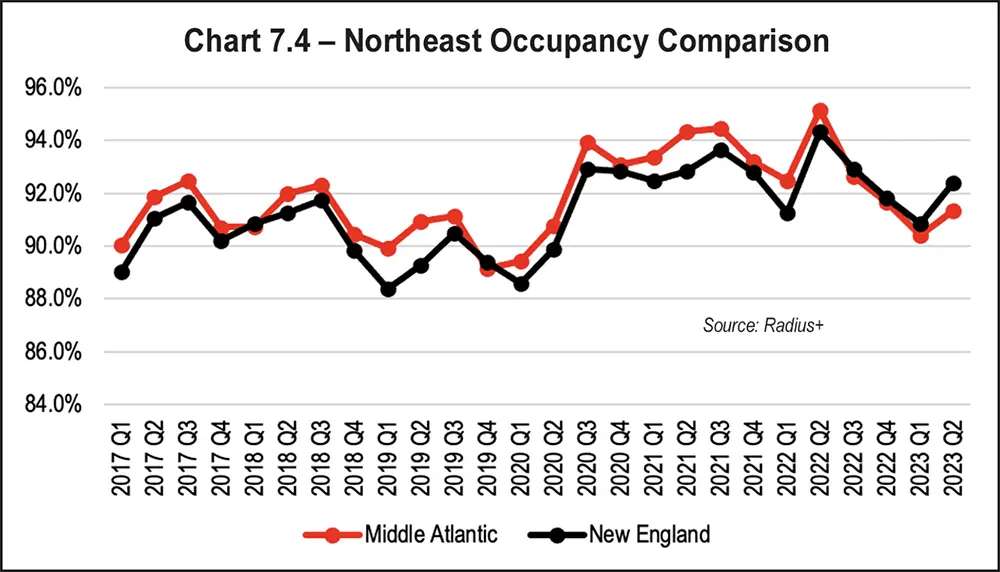

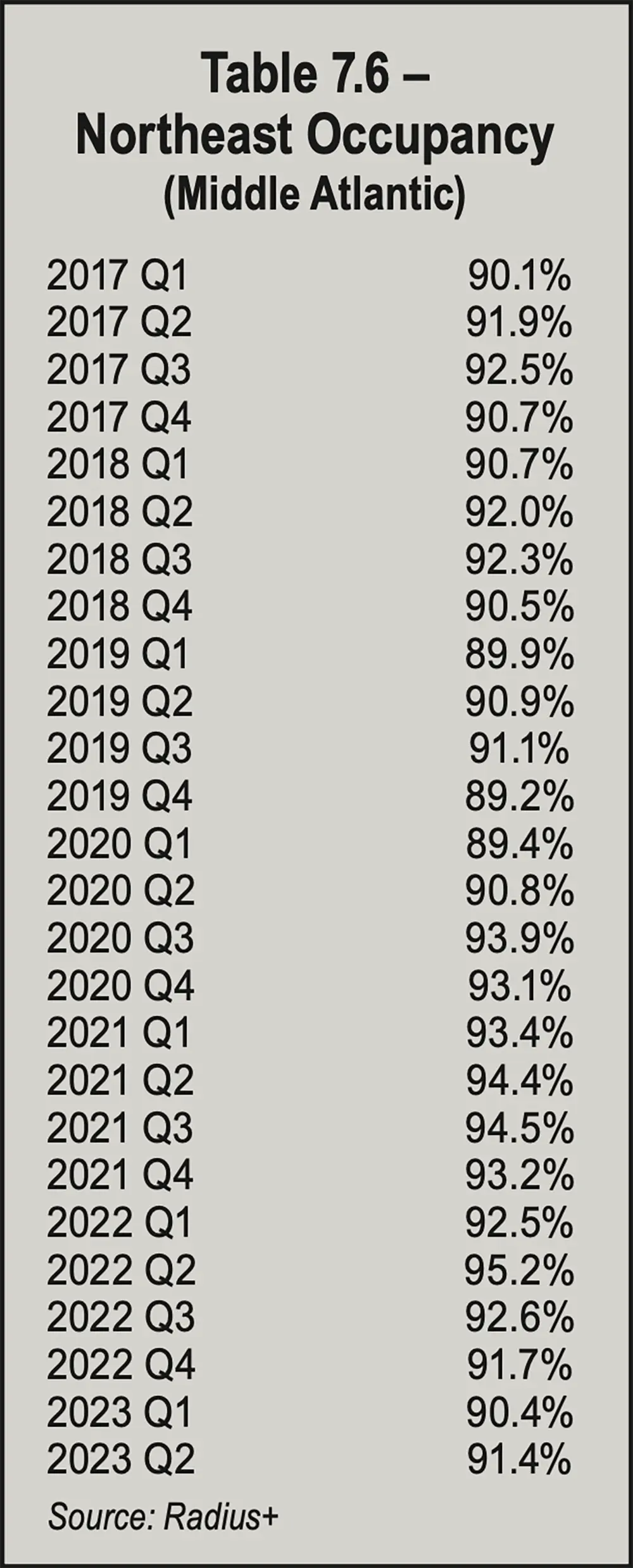

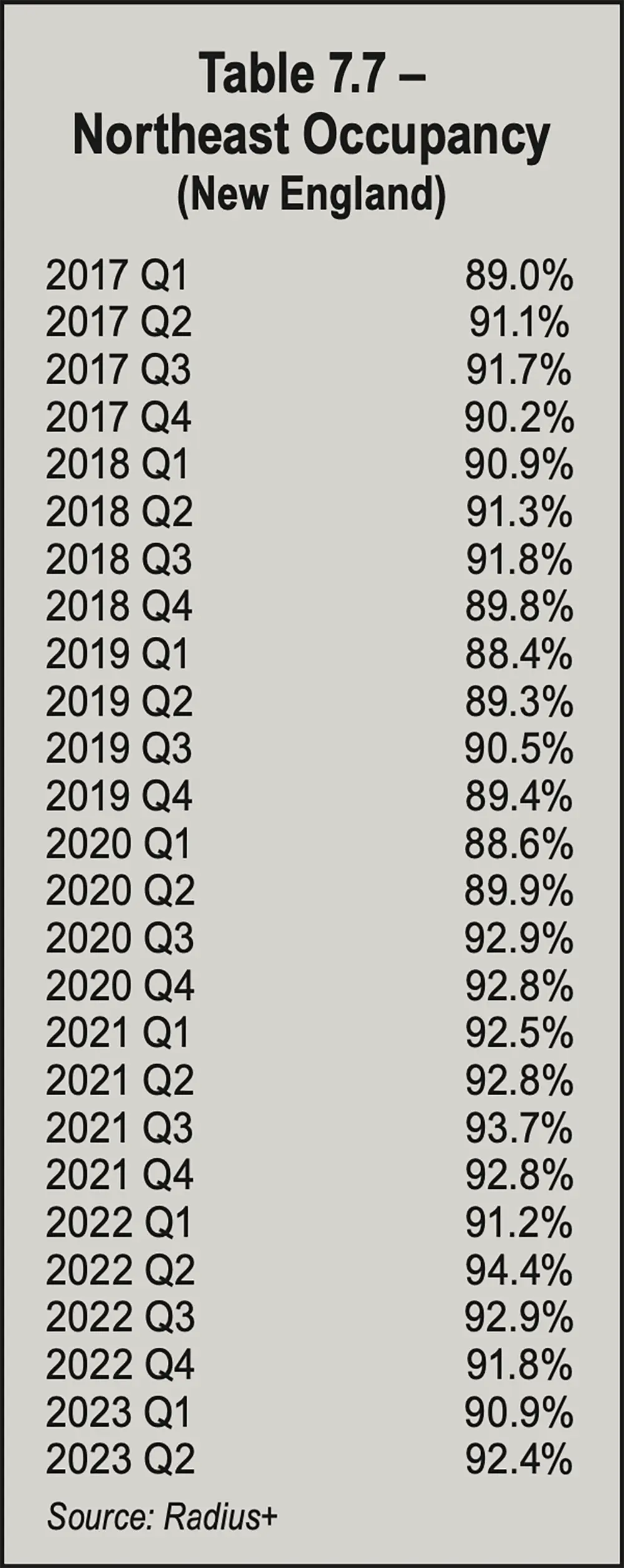

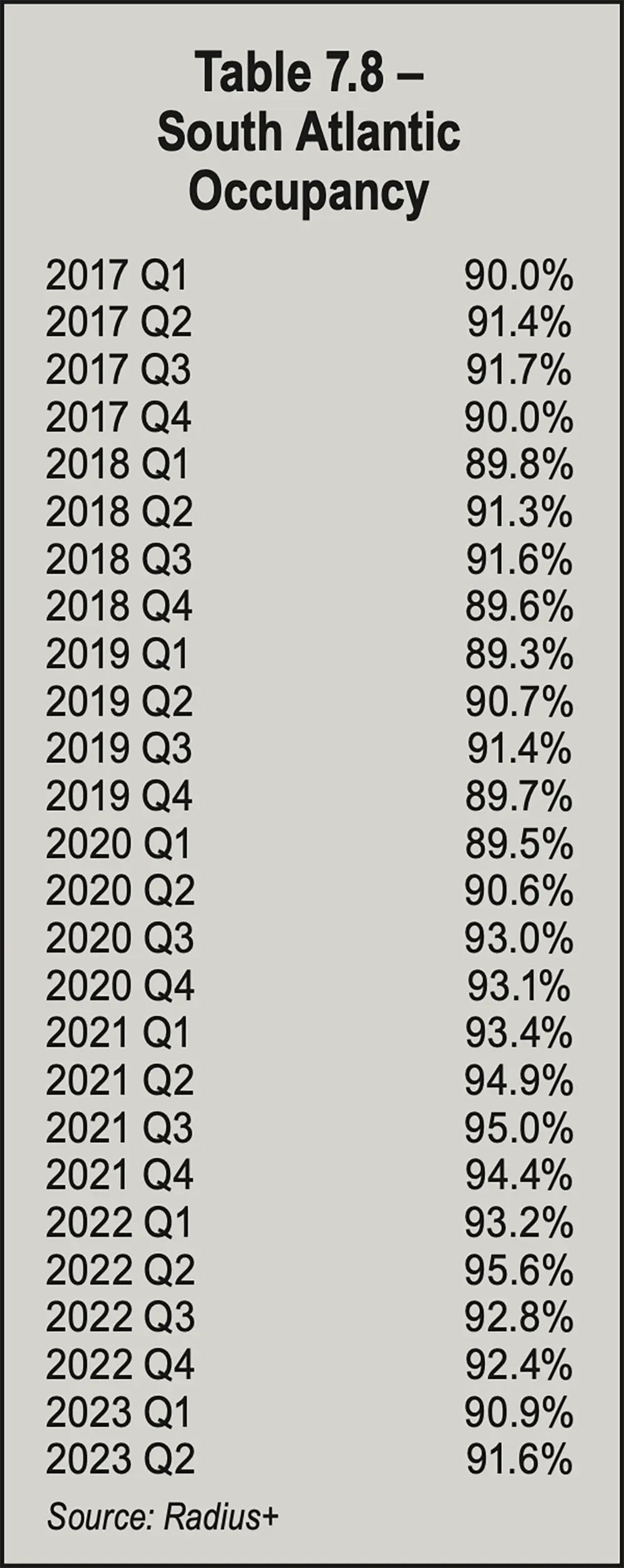

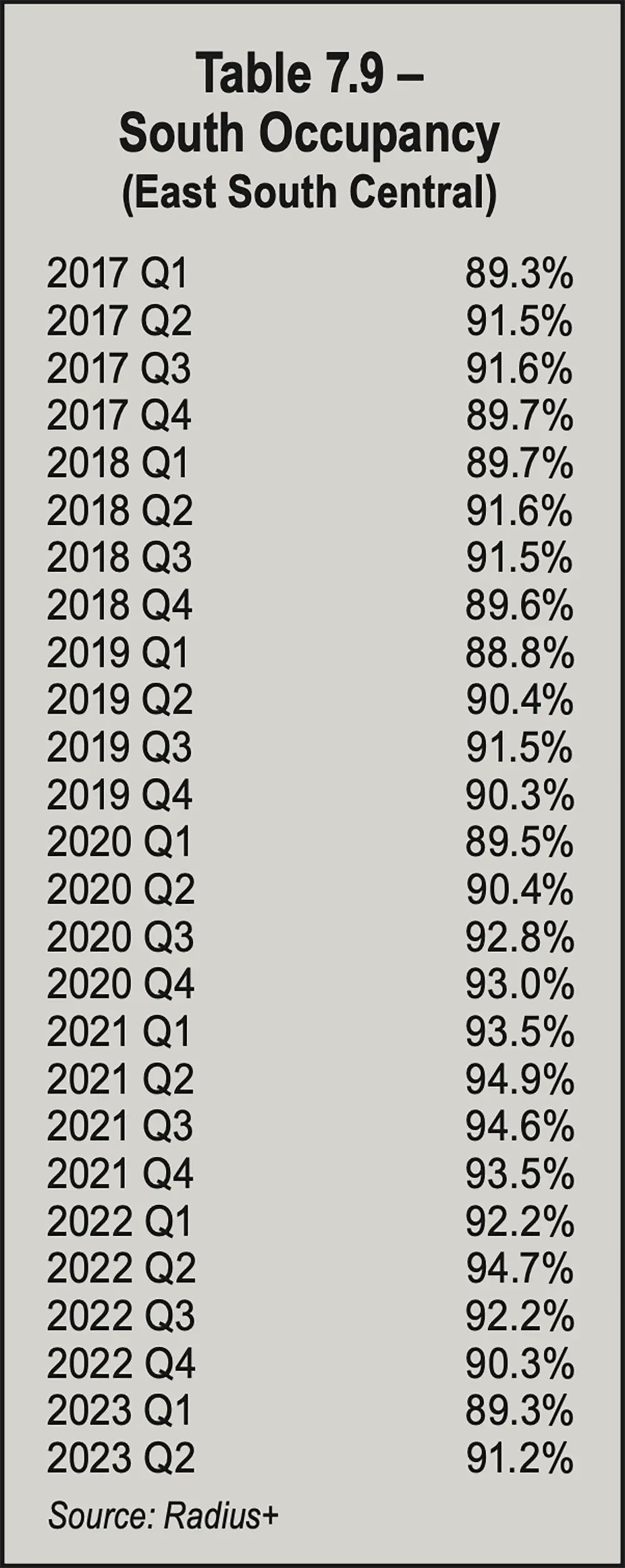

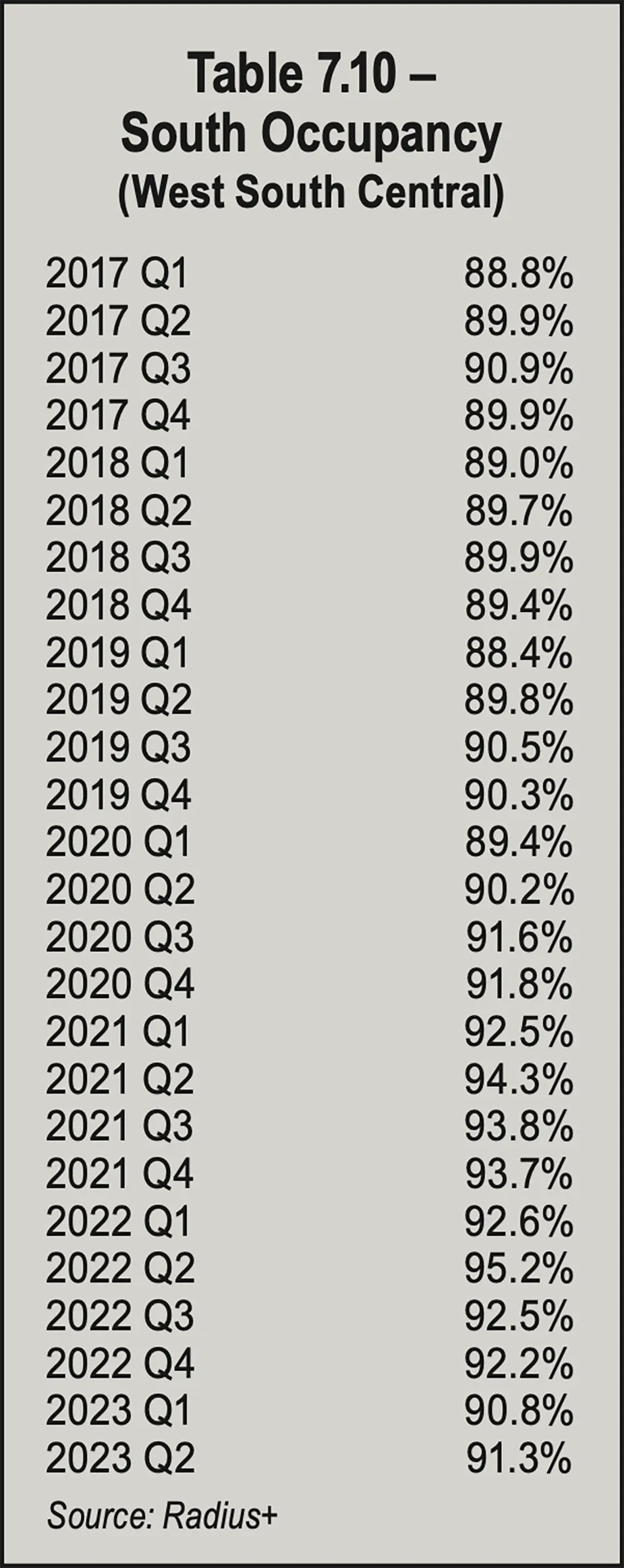

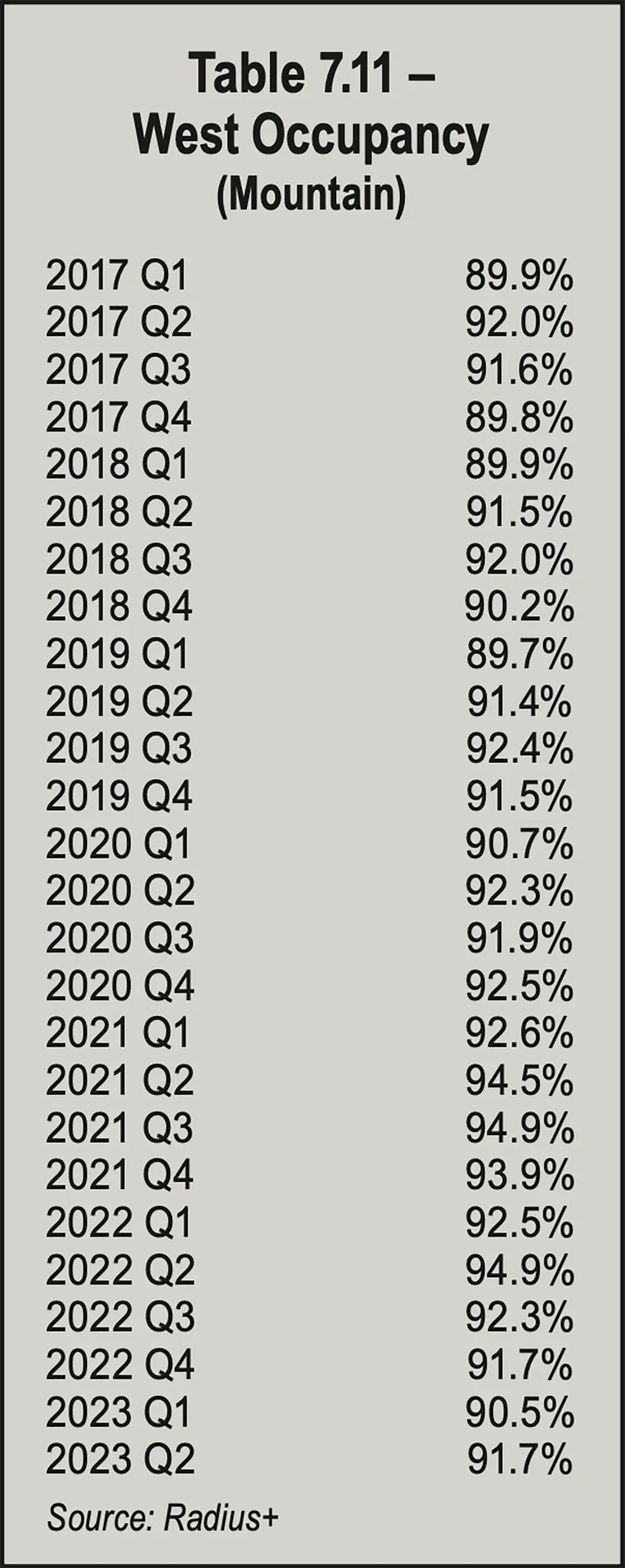

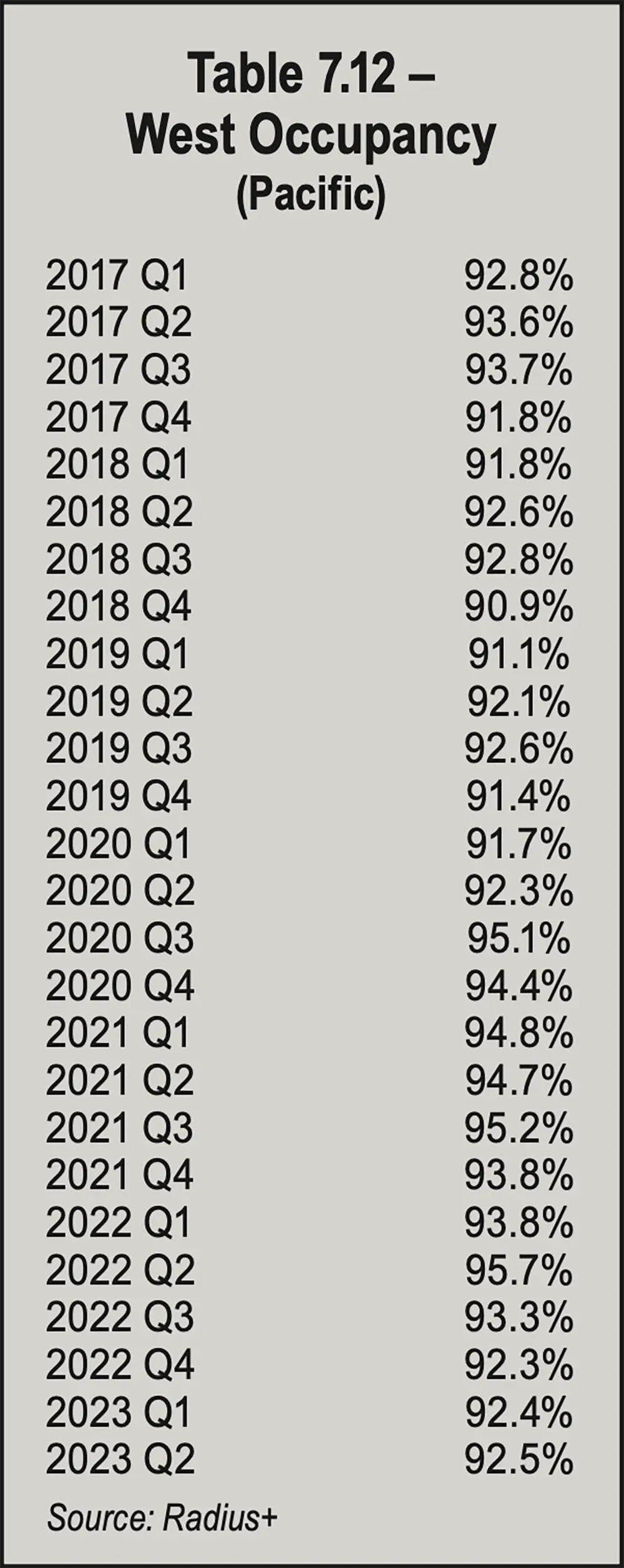

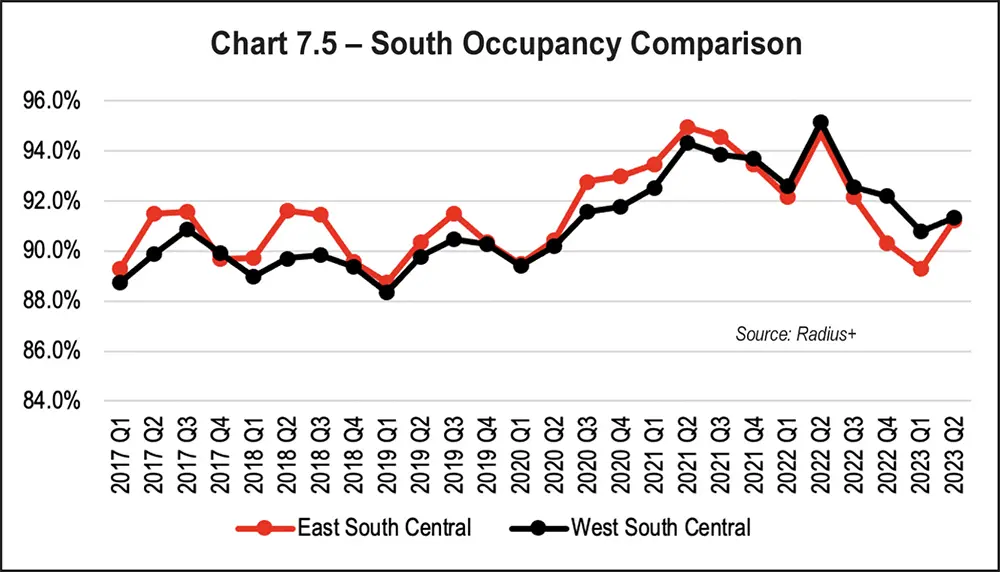

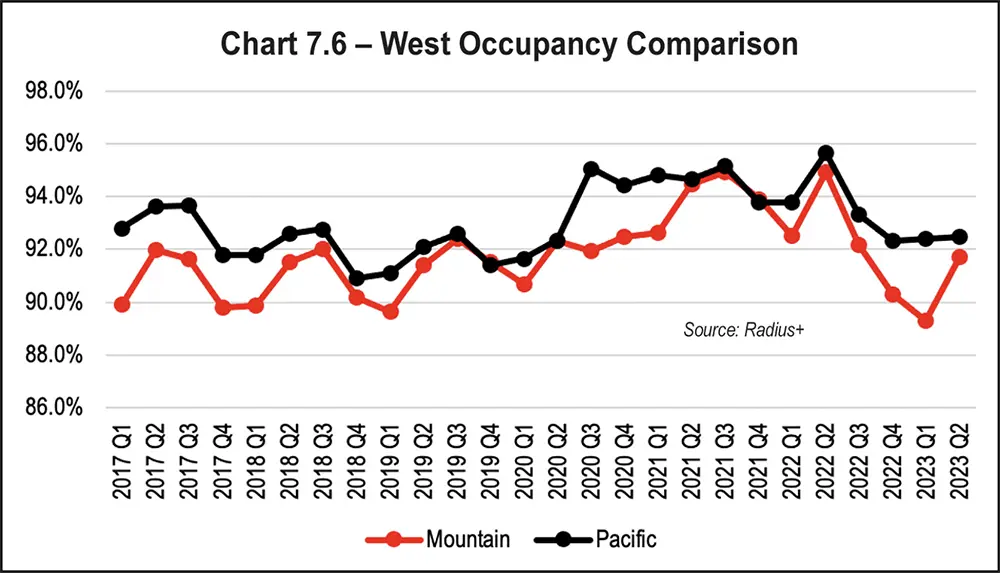

As shown in Table 7.3 and Chart 7.2 on the opposite page, occupancy fell in Q2 2023 to 92.4 percent from 95.3 percent in Q2 2022 in the Midwest region’s East North Central area. It fell to 87.9 percent from 95 percent in the Midwest’s West North Central area. It dropped to 91.4 percent from 95.2 percent in the Northeast region’s Middle Atlantic area and decreased 2.0 percent to 92.4 percent from 94.4 percent in the Northeast region’s New England area. It fell 4.0 percent to 91.6 percent from 95.6 percent in the South Atlantic region, which is not divided into subregions. The rate declined 3.5 percent to 91.2 percent from 94.7 percent in the South region’s East South Central area and fell 3.9 percent to 91.3 percent from 95.2 percent in its West South Central area. Occupancy rates also dropped in the West, with the Mountain area reporting a 3.2 percent decrease (91.7 percent from 94.9 percent) and the Pacific area experiencing a 3.5 percent decrease (92.5 percent from 95.7 percent).

The Midwest’s North Central area’s occupancy rates from Q1 2017 through Q2 2023 were in the 90s for 19 quarters and in the 80s for seven quarters. Q2 2022 showed the highest quarterly increase, at 3.2 percent, from Q1 2022. The greatest quarterly decrease was 2.8 percent from Q2 to Q3 2022. See Table 7.5 on page 65.

The lowest rate for the period was 89.2 percent in Q4 2019, one of three quarters in the 80s for the period, along with 89.9 percent in Q1 2019 and 89.4 percent in Q1 2020. All other quarters in the period were in the 90s. The greatest quarterly increase, 3.1 percent, was from Q2 to Q3 2020. The greatest quarterly decrease, 2.6 percent, was from Q2 to Q3 2022.

From Q1 2017 through Q2 2023, occupancy rates rose from Q1 to Q2 and Q2 to Q3 (except when it fell from Q2 2022 to Q3 2022) and fell from Q3 to Q4.

Table 7.7 on page 66 shows the Northeast’s New England area’s high rate for the period was 94.4 percent in Q2 2022. The low rate was 88.4 percent in Q1 2019. Q2 2023 rose 1.5 percent from 90.9 percent the prior quarter and rose 1.1 percent from 91.8 percent in Q4 2022. Occupancy rates rose from Q1 to Q2 and from Q2 to Q3 (except in 2022) and decreased from Q3 to Q4 throughout the period. Q1 fell from Q4 five times and rose once. Occupancy rates were in the 80s for seven quarters and in the 90s for 19 quarters.

As Chart 7.4 on page 66 shows, occupancy rates in the Middle Atlantic were higher than in New England in 20 quarters and lower in six quarters (Q1 2018, Q4 2019, and Q3 2022 through Q2 2023).

Occupancy rates increased throughout the period from Q1 to Q2. Rates rose from Q2 to Q3 three times (2017, 2019, and 2020) and fell three times (2018, 2021, and 2022). Rates fell from Q3 to Q4 except in 2020, when they rose. From Q4 to Q1, the rate fell four times, rose once, and was unchanged once. Occupancy was in the 90s for 19 quarters and in the 80s for seven quarters.

Chart 7.5 on page 67 shows that for the period from Q1 2017 through Q2 2023, the East South Central area had higher occupancy rates than the West South Central 17 quarters and lower rates in eight quarters. The rates were the same (90.3 percent) in Q4 2019.

For the entire period, rates increased from Q1 to Q2, increased three times and decreased three times from Q2 to Q3, decreased five times and increased once from Q3 to Q4, and decreased three times and increased three times from Q4 to Q1. For the whole period, occupancy rates were in the 80s in four quarters and the 90s in 22 quarters.

Occupancy rates from Q1 2017 through Q2 2023 in the West region’s Pacific area, shown in Table 7.12, peaked in Q2 2022 at 95.7 percent. The lowest rate was 90.9 percent in Q4 2018. Q1 2017 had a 92.8 percent rate. Q2 2023’s 92.5 percent rate was the result of two quarterly increases of 0.1 percent (from 92.4 percent in Q1 2023 and 92.3 percent in Q4 2022. The greatest quarterly increase was 2.8 percent from Q2 to Q3 2020. Q2 2022 to Q3 2022 had the greatest quarterly decrease (2.4 percent).

Throughout the period, occupancy rose from Q1 to Q2, except in 2021. Rates rose from Q2 to Q3, except when they fell in 2022. Rates fell from Q3 to Q4 throughout the period. Rates rose from Q4 to Q1 four times; they remained unchanged from Q4 2017 to Q1 2018 (91.8 percent) and Q4 2021 to Q1 2022 (93.8 percent). Occupancy rates were in the 90s in all quarters. See Table 7.12 on the opposite page.

Chart 7.6 on the opposite page compares the Mountain and Pacific areas of the West region. It shows the Pacific area had higher occupancy rates from Q1 2017 through Q2 2023 in every quarter except Q4 2019, Q4 2021, and Q2 2020 (tied at 92.3 percent).